Florida Legend, Tennessee Roots

He became an icon at UF, but the legend of Steve Spurrier began in a small east Tennessee town. Six decades later, Johnson City still means as much to Spurrier as he means to his hometown.

Three summers ago, Steve Spurrier and one of his daughters, Amy Moody, stood at the field now named after him, where acres of green grass and brick buildings hold his core memories.

Moody watched as her father, who would become a Heisman Trophy winner and the winningest coach in Florida football history, returned for his 60-year class reunion at Science Hill High School in Johnson City, Tennessee. They stopped by every building he set foot in as a child and every room that shaped him into the athlete and person he is.

“He never forgets the people who believed in him or who gave him a chance,” Moody said. “That all started right [here].”

Johnson City made Spurrier. Even something as simple as the tomato sandwich his mom made him every day brings Spurrier back to the place he first learned how to throw a football.

At his restaurant in Gainesville in early November, a wide smile grew on Spurrier's face as he talked about some of his fondest memories, a lifetime since his last high school game.

“I owe my career as a player and as a coach to Johnson City, Tennessee and Science Hill High School,” Spurrier said.

While Florida cemented his legacy, his hometown in Tennessee is where it began.

Growing up in the foothills

An uneventful two-hour car ride from Knoxville, Johnson City rests at the foothills of Appalachia, rooted with a deep college aesthetic.

While the population has boomed over the years from 31,200 in the 1960s to over 74,000 in 2024, the community remains as close as ever. Only a street separates one of two middle schools and the sole high school in the area. Johnson City is its own school district, with Science Hill High School at the center of it.

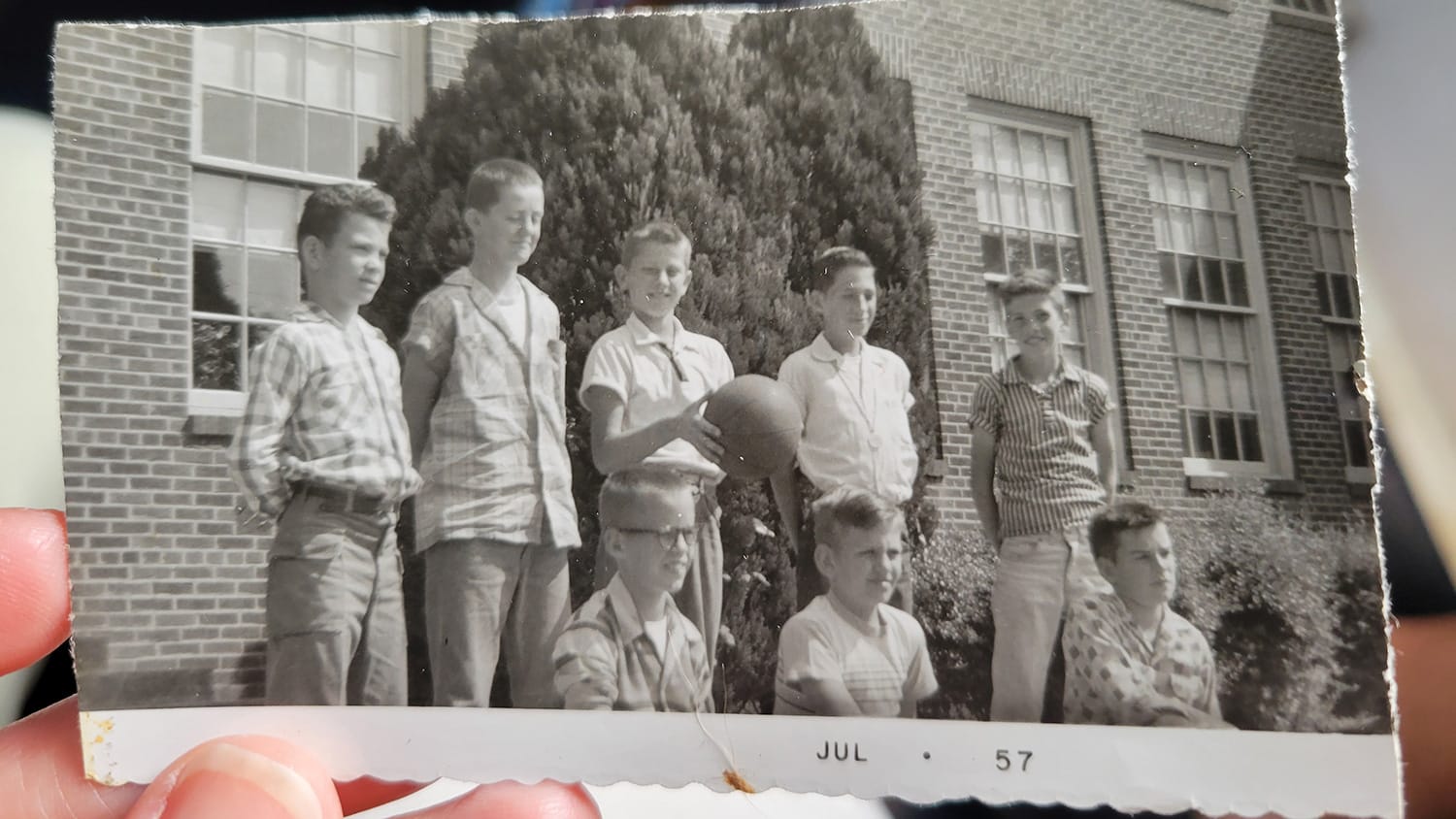

Everyone in the area typically knows each other and ends up going to the same school. That was also the case in the ‘60s. Spurrier and his family moved from place to place, landing in Johnson City in 1956 when he was 11. Spurrier attended Science Hill from 1960-63.

Spurrier’s family were no strangers in the town. His dad, Graham Spurrier, preached at Calvary Presbyterian Church while his mother, Marjorie, instructed the choir.

“The small town claimed him,” Moody said. “He lived there long enough that he was theirs.”

Spurrier's parents were dedicated to him and believed in what he wanted to do.

As a child, he went to church every day it was open, morning and evening. His grandfather always told him that Sundays were supposed to be days of rest, but Spurrier disagreed. He eventually bargained with his mom, and she let him start kicking the football before and after church sessions.

Lucky No. 11

Despite winning a Heisman with the Gators in 1966 and a national championship as the head coach at Florida coach 30 years later, Spurrier will always say a high school baseball game at Science Hill was one of his most memorable athletic moments.

He pitched for the Hilltoppers against their rival Kingsport, which they had lost to twice in the regular season, again in the state tournament. He started the game, and they went on to win the championship.

Spurrier could tell every little detail like it was yesterday, recounting memories from that 1962 title team and the school’s run the year after to go back-to-back. He was undefeated as a starting pitcher, going 25-0. And one of the school's two championships in the Spurrier era ended dramatically.

After falling behind 4-2, the Hilltoppers tied the score in the eighth inning. None other than Spurrier stepped up to the plate with the winning run on base.

“We got a guy on first with two outs," Spurrier recalled. "I hit a little blooper over the first baseman’s head down the right-field line, and Tony Bowman scored from first base. He legged it all the way around, and we won 5-4.”

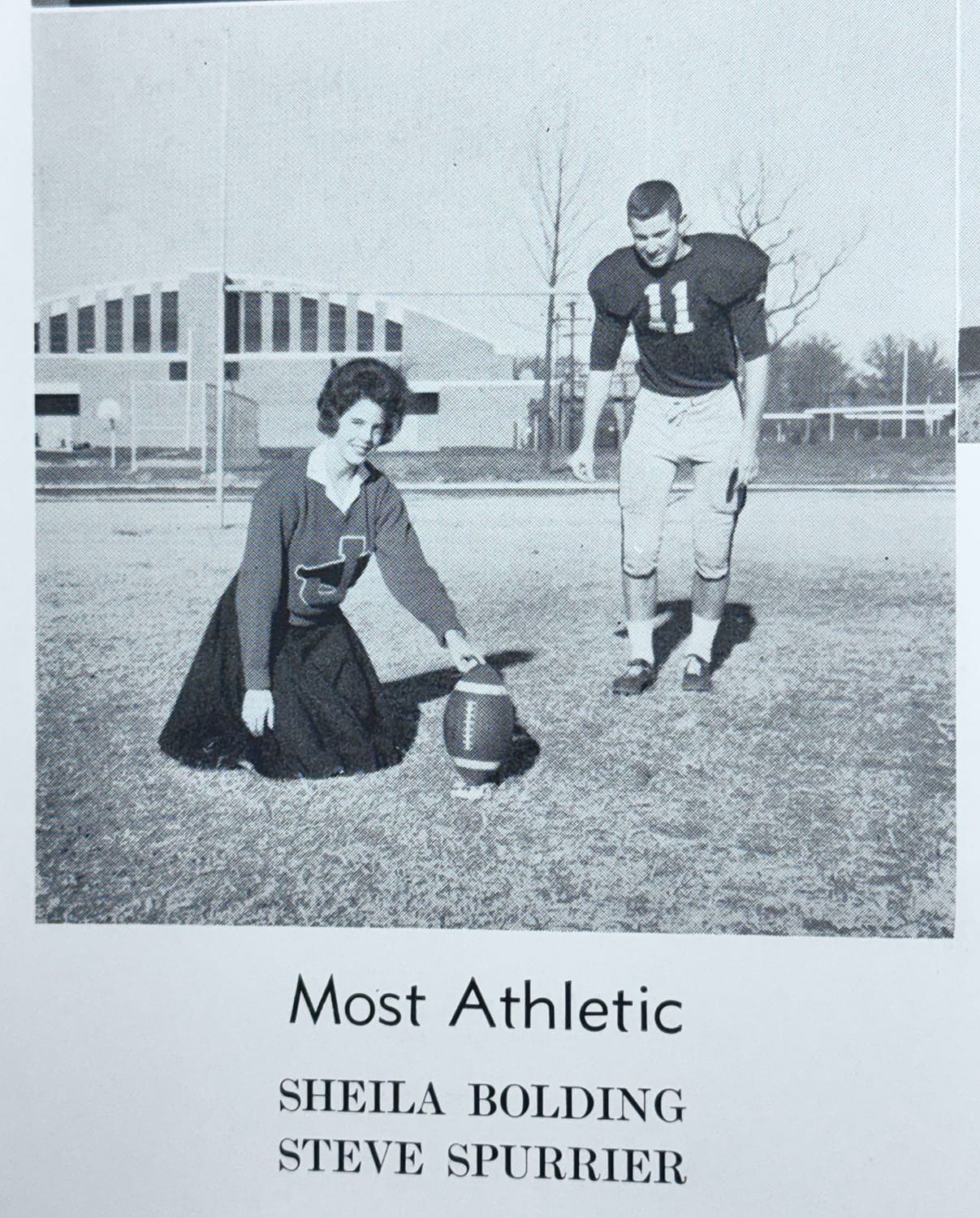

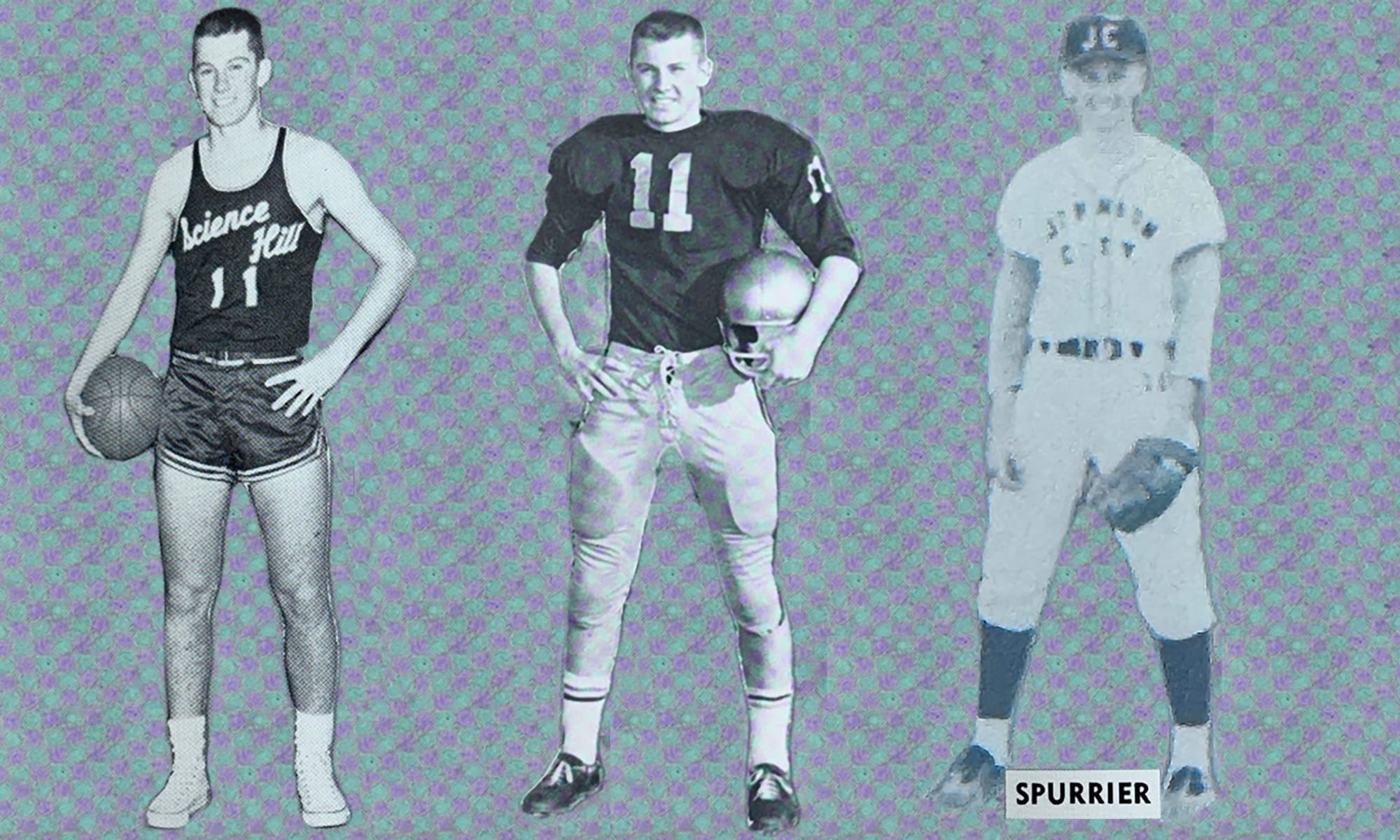

In a time when athletes played several sports in school, Spurrier was no exception. He was named to the all-state team in three sports: football, basketball and baseball.

Spurrier credits all three of his coaches – Kermit Tipton, John Bross and Alvin Little — to his athletic development. Tipton, the football coach, was temperamental, he said. Bross, his baseball coach, barely said a word and Little, his basketball coach, was always active.

“I learned a lot from all three of them,” he said. “Tremendous three coaches.”

In every sport he played, there was one thing in common: Spurrier wore the number 11. That stuck throughout his entire career – it followed him to Florida and to the NFL. It was merely an initial choice based on availability, but it became his thing.

“Lucky No. 11 is what it was,” he said.

In his senior year as Science Hill's quarterback, Spurrier threw for 16 touchdowns and was named an All-American. In hoops, he averaged 22 points per game and was also the District 1 basketball tournament MVP that year.

Thomas Hager, a baseball and basketball teammate and now the longest-serving member of the Johnson City school board, said the team’s plans always focused on Spurrier.

“Our coach’s philosophy was to get the ball to him," Hager said. "And in one particular game against a pretty good team, he scored more points than the other team himself."

He believes Spurrier could have played basketball in college if he wanted to, even in the SEC. Former teammate Harry Gibson agreed: “Whatever he did, he was a winner.”

Home away from home

Coming out of high school, Tennessee was never a fit for Spurrier, he admits, because of the wing-T offense it operated at the time. The Volunteers ran the ball extensively through heavy sets, which wasn’t his game.

Florida came into the picture late, after basketball season. But a 72-degree Gainesville day in March didn't hurt. Coach Ray Graves sold him, and the rest is history.

With the Gators, Spurrier won the Heisman in his senior season, throwing for 2,012 yards and 16 touchdowns. But he never faced Tennessee while under center.

Once his playing days ended, Spurrier never considered coaching in Knoxville. Part of Florida’s recruiting pitch to a high school Spurrier was that if he played well enough in college, he’d be able to stay in the Sunshine State. That’s exactly what happened.

Spurrier returned to Gainesville to become the Gators’ coach in 1990 after three seasons at Duke.

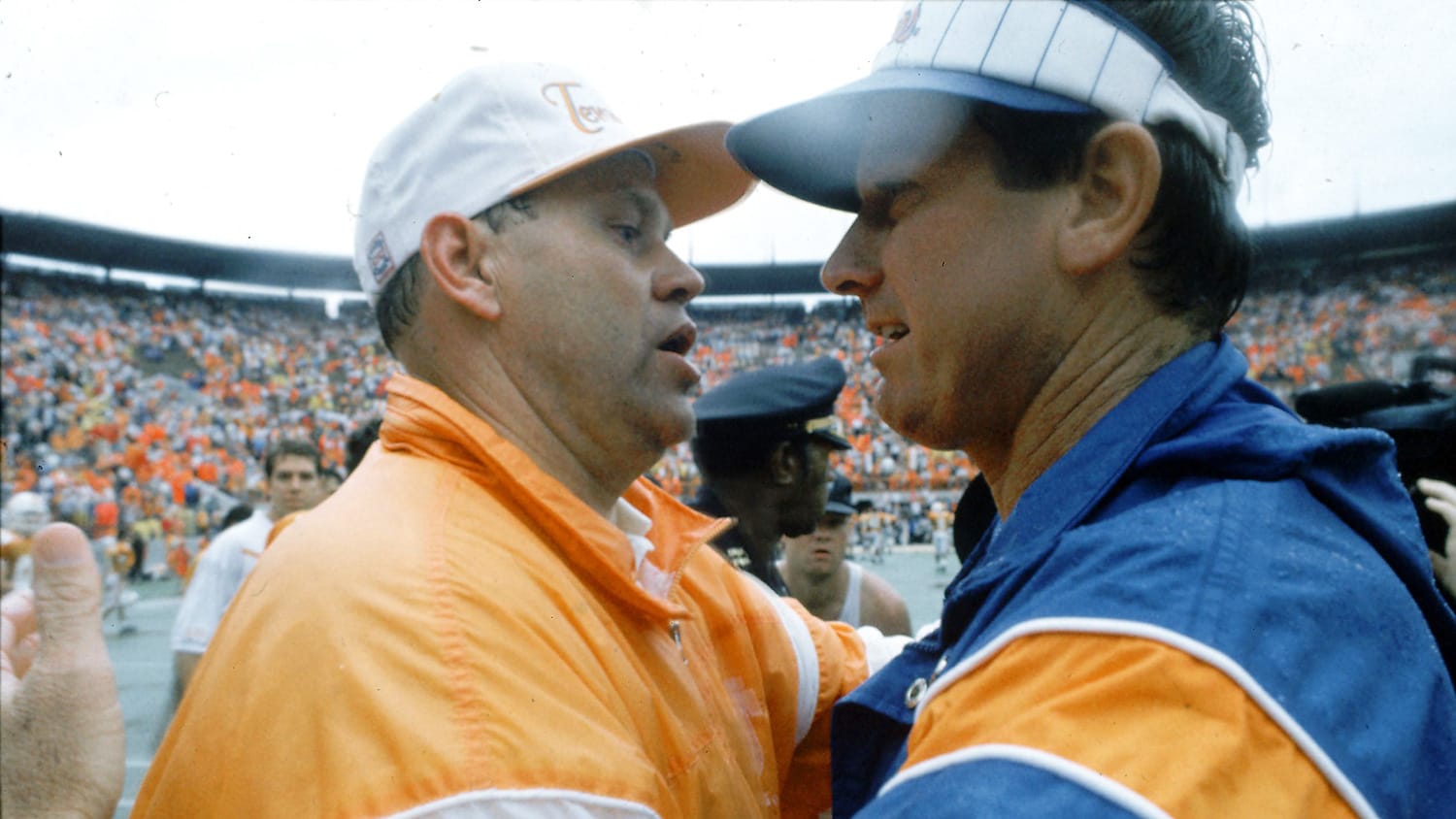

And one of Florida's biggest rivals almost immediately became ... Tennessee. The SEC split into East and West divisions in 1992 after Arkansas and South Carolina were added to the conference. That same year, Phil Fulmer became the head coach of the Volunteers, and the rivalry took off.

Each September, the matchup held the nation at its fingertips. The winner of the game almost always would go on to win the SEC East and make the conference championship game. This happened in all but three years in Spurrier’s tenure.

As a coach, Spurrier went 8-4 against Tennessee while at Florida, including five straight wins from 1993-97. Florida’s 62-37 comeback victory in 1995 — after trailing 30-14 — is among the series’ most notable. The following season, the Spurrier-led Gators outdueled Peyton Manning and the No. 2 Vols 35-29 in Neyland Stadium – a victory that would help propel UF to its first national championship.

Because of Spurrier, Florida-Tennessee quickly grew into one of the nation's most heated rivalries at the time. Spurrier’s squads frequently stood between Tennessee and national success. And he loved to tweak the Vols off the field, too. The annual showdown also was the catalyst for some memorable Spurrier one-liners.

“Can’t spell Citrus without UT,” he once joked.

Spurrier loved to talk, and he backed it up by winning. In 12 seasons, Spurrier was the most successful coach in UF history, finishing with a 122-27-1 record, six SEC championships and that 1996 national title.

Despite pummeling the Volunteers, the mutual admiration between Spurrier and Johnson City is eternal. While some locals wish he had attended the University of Tennessee, his hometown still claims him as one of theirs.

“We're proud as a city to have a guy that is not just a Heisman Trophy winner, but one of the best college coaches that's ever been and a national championship winner,” said Science Hill coach Stacy Carter, who has lived in Tennessee all his life.

The tradition continues

Back home in Johnson City, his name remains: on the field, the scoreboard, signs at Science Hill and even on commercials. Carter even campaigned for a sign that reads “Home of the Heisman Trophy Winner” when entering the city.

Spurrier’s still a regular in Johnson City. He returns every 10 years for his class reunions. He’s one of the first to talk. He’s gone back for retirements and funerals, as well.

“That’s where I was fortunate enough to develop as a player and come on to Florida,” Spurrier said. “So I feel like I owe it back to my community and my high school to help the players, students and everyone there.”

In 2016, his high school also renamed its football field to Steve Spurrier Field at Kermit Tipton Stadium. Science Hill tried to retire his number, but he made them un-retire it. He wants other players to leave their legacy. It’s now been a tradition for each starting quarterback at the school to wear No. 11. Like he did at Science Hill, Spurrier unretired his jersey at Florida when he was the ’Head Ball Coach’ and first let former linebacker Ben Hanks wear it.

“We have had a bunch of good quarterbacks wear the number, and it’s been an honor and tradition to do that,” Carter said.

When funding was on the line for a brand new field house, Carter said Spurrier and his former teammates rose to the occasion to make sure it happened. Despite not being on the agenda to speak, Spurrier and his former teammate Carleton “Cotty” Jones threatened to pull their funding money, Carter said, if the district didn’t advance the construction of the field house.

“[He] walked out of the room and everybody started going crazy,” Carter said. “That was the catalyst that got us the field house and the weight room and everything.”

In 2015, the new field house and weight room opened, setting the facilities and standard at Science Hill to a new level. Spurrier, Jones and Gibson, among other teammates, have donated thousands over the years in support of their alma mater, including to the Kermit Tipton Scholarship fund each year. Three players are annually awarded $6,000 based on coach recommendations and criteria.

“That’s where I came from, and I’m fortunate to be in a position financially to give a little bit back,” Spurrier said. “They do a good job of helping athletes go to college and things like that.”

Today, Spurrier remains a fixture at UF. At 80, he continues to host a radio show and frequently attends Gators sporting events. Even the popular Gainesville restaurant that bears Spurrier's name connects back to his hometown. On the menu? A tomato grilled cheese sandwich that features fruit shipped directly from Johnson City.

Even now, 570 miles away from the growing town he once called home, Spurrier’s ties to Johnson City and the Science Hill community remain entrenched in who he is.

“When I talk to him, the first thing he always asks is, how’s the football team doing?” Hager said. “And then how’s the high school?” •